The Ars Nova (c.1300 - c.1400)

We cannot start talking about Ars Nova without going through the

development of the Motet in the thirteenth-century. The Motet is one of the most important forms

of polyphonic music that changes

greatly with each historical period about 1220 to 1750. Originally, motet was Roman Catholic Church music with Latin

biblical text sung in two parts, one of which was taken from Gregorian Chant.

After that parisian

composers of the early 13th century experimented with the addition of newly written

texts (secular) to the most progressive melismatic polyphony, including the

caudas of conductus and the melismas of organum. This is when the Motet came to

exist, witch was basically an application of a poetic text to the duplum of a

clausula, in other terms it was essentially ‘troped discant passages’ or

‘troped clausulas” with many as three as three different secular texts

simultaneously and even a refrain.

Near 1400, a new musical revolution called the Ars Nova (New

Art) brought the Motet an increasing use of a single text and a

treble-dominated style with one principal melody and two supporting parts. The concept of Ars

Nova is based on the enormous new range of musical expression made

possible by the notational techniques explained in Philippe de Vitry's treatise

Ars Nova (c1322). Characteristics

of this style include the reject of the preeminence of triple rhythm (that

gave origin to the new rhythmic notation called mensuration), an increasing

tendency to view music as an autonomous realm rather than a reflection of

spiritual or philosophical ideas, the complexities of the isorhythm were

explored more in depth (talea an color), although the tradition to write about

courtly love with secular texts was kept by many composers of the fourteenth

century. A good example of these love songs is Guillaume de Machaut’s Rose, liz, printemps, verdure:

In this composition Machaut’s used the fixed

form Rondeau, since in the new movement of Ars Nova the composers did not use

cantus firmi but freely composed all the voices they had to develop some

structural procedures, know as forms

fixes. The form of the Rondeau was AB aA ab AB. Another peculiar thing about this composition is the extensive use of syncopation, probably to give it a more dance-like feel, even though you can still feel the duple meter but the syncopes give you a ambiguous sense of rhythm.The motivic figures caught my attention, because they are felt in the old triple meter, could it be an symbolic allusion to the divine perfection on the middle of a love song? Another symbolic possibility I found in this piece, the adjectives that Machaut uses for his "beautiful lady" are always seven, with a pause on the sixth adjective to reinforce the seventh one. I could be going on a totally wrong direction here, but isn't the number seven the Egyptian symbol for perfection? For my surprise the last word of the music has seven letters After thinking about these two symbolic possibilities I counted the numbers of measures, and guess what? The answer is 37 ... Machaut was a renowned poet, which had a relationship with a young girl named Peronne (seven words), it could be also an allusion to her instead. Hmm...

References:

Seaton, Douglass. Ideas and Styles in the Western Musical Tradition. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Pub., 1991. Print.

Latham, Alison. The Oxford Dictionary of Musical Terms. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. Print.

Burkholder, James Peter, and Claude V. Palisca. Norton Anthology of Western Music.Vol. 1. New York: W. W. Norton, 2006. Print.

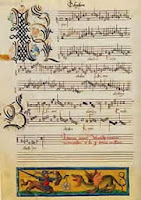

| Example of Mensuration Notation |

| Guillaume de Machaut (ca. 1300 - 1377) |

References:

Seaton, Douglass. Ideas and Styles in the Western Musical Tradition. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Pub., 1991. Print.

Latham, Alison. The Oxford Dictionary of Musical Terms. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. Print.

Burkholder, James Peter, and Claude V. Palisca. Norton Anthology of Western Music.Vol. 1. New York: W. W. Norton, 2006. Print.