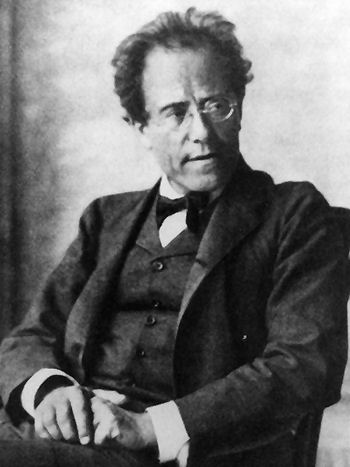

Late Romanticism (1850–1900) - Mahler

The Late-Romantic period saw the blossoming of self-expression in music. By the mid-19th century, the Romantic impulses of subjective expression and organic unity had become fully internalized by most composers, leading to more pronounced applications of both in their music.

By the closing decades of the 19th century, the developments (explained in my previous blog post) began to stretch to an extreme extend, many composers felt that by the time Wagner died, Romanticism had reached its limits of expression. As heard in the lengthy symphonies and orchestral works of Wagner's "successors", such as Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss we can see that there were nowhere else to go from that, and this led in many ways to a crisis in music. Composers started to look around for new ideas, and those were the kinds of experiments that defined the coming Impressionist and Modern eras.

As a brass player and a lover of his symphonies, I have to talk about Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) and his symphonies.

As a brass player and a lover of his symphonies, I have to talk about Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) and his symphonies.

Mahler was primarily known during his lifetime as a conductor and director of operas. His symphonies

made little impact until the last ten years of his life. It was not until the 1960s and 1970s, when Mahler's symphonies become a staple of concert halls all over the world. His epic-scale symphonies and orchestral song-cycles provided an important link between the late 19th Century Romantic and early Modern periods.

Mahler once said: To write a symphony means, to me, to construct a world" From that he pursued to expand the scope and range of the symphony to the greatest possible extent. This expansion of scope can be seen in the explosion of orchestral forces engaged and in the artistic deeply expressive power. The major influence on his works was not a symphonic composer it was Wagner! According to Mahler, Wager was the only composer, after Beethoven to truly have made progress with his music.

Mahler combined the ideas of Romanticism, including the use of program music, and the use of song melodies in symphonic works, with the resources that the development of the symphony orchestra had made possible. The result was to extend, and eventually break, the understanding of symphonic form, as he searched for ways to expand his music.

He was deeply spiritual and described his music in terms of nature very often. This resulted in his music being viewed as extremely emotional for a long time after his death.

My favorites symphonies from his 'second period', Symphonies Nos. 5 to 7. Mahler manifest an increased severity of expression and a growing interest in non-standard instrumentation. Like the use of cowbells, deep bells, a hammer, cornet, tenor horn, mandolin and guitar.

My favorites symphonies from his 'second period', Symphonies Nos. 5 to 7. Mahler manifest an increased severity of expression and a growing interest in non-standard instrumentation. Like the use of cowbells, deep bells, a hammer, cornet, tenor horn, mandolin and guitar.

Another amazing thing about Mahler, that I was lucky enough to learn during my Music History class this year, is that Mahler belongs to a select list of composers that freely interconnected their work. Musical interconnections in Mahler's music can be heard to exist all over: between symphonies and symphonies, and between symphonies and songs. They all that seem to bind them together into a larger narrative history. For example, a trumpet line from the first movement of the fourth opens the fifth symphony. And a 'tragic' harmonic gesture repeatedly heard in the sixth symphony (a major chord declining into a minor) makes a striking reappearance in the seventh symphony. The rising melody line from the adagietto on the fifth symphony makes an appearance in its finale, and again in revised form in the finale of the seventh symphony. Furthermore, in his first symphony Mahler borrowed material from his song cycle Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen.

Here is a video of one of my favorite Mahler symphonies, Symphony N.5:

By the closing decades of the 19th century, the developments (explained in my previous blog post) began to stretch to an extreme extend, many composers felt that by the time Wagner died, Romanticism had reached its limits of expression. As heard in the lengthy symphonies and orchestral works of Wagner's "successors", such as Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss we can see that there were nowhere else to go from that, and this led in many ways to a crisis in music. Composers started to look around for new ideas, and those were the kinds of experiments that defined the coming Impressionist and Modern eras.

As a brass player and a lover of his symphonies, I have to talk about Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) and his symphonies.

As a brass player and a lover of his symphonies, I have to talk about Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) and his symphonies.Mahler was primarily known during his lifetime as a conductor and director of operas. His symphonies

made little impact until the last ten years of his life. It was not until the 1960s and 1970s, when Mahler's symphonies become a staple of concert halls all over the world. His epic-scale symphonies and orchestral song-cycles provided an important link between the late 19th Century Romantic and early Modern periods.

Mahler once said: To write a symphony means, to me, to construct a world" From that he pursued to expand the scope and range of the symphony to the greatest possible extent. This expansion of scope can be seen in the explosion of orchestral forces engaged and in the artistic deeply expressive power. The major influence on his works was not a symphonic composer it was Wagner! According to Mahler, Wager was the only composer, after Beethoven to truly have made progress with his music.

Mahler combined the ideas of Romanticism, including the use of program music, and the use of song melodies in symphonic works, with the resources that the development of the symphony orchestra had made possible. The result was to extend, and eventually break, the understanding of symphonic form, as he searched for ways to expand his music.

He was deeply spiritual and described his music in terms of nature very often. This resulted in his music being viewed as extremely emotional for a long time after his death.

My favorites symphonies from his 'second period', Symphonies Nos. 5 to 7. Mahler manifest an increased severity of expression and a growing interest in non-standard instrumentation. Like the use of cowbells, deep bells, a hammer, cornet, tenor horn, mandolin and guitar.

My favorites symphonies from his 'second period', Symphonies Nos. 5 to 7. Mahler manifest an increased severity of expression and a growing interest in non-standard instrumentation. Like the use of cowbells, deep bells, a hammer, cornet, tenor horn, mandolin and guitar.Another amazing thing about Mahler, that I was lucky enough to learn during my Music History class this year, is that Mahler belongs to a select list of composers that freely interconnected their work. Musical interconnections in Mahler's music can be heard to exist all over: between symphonies and symphonies, and between symphonies and songs. They all that seem to bind them together into a larger narrative history. For example, a trumpet line from the first movement of the fourth opens the fifth symphony. And a 'tragic' harmonic gesture repeatedly heard in the sixth symphony (a major chord declining into a minor) makes a striking reappearance in the seventh symphony. The rising melody line from the adagietto on the fifth symphony makes an appearance in its finale, and again in revised form in the finale of the seventh symphony. Furthermore, in his first symphony Mahler borrowed material from his song cycle Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen.

Here is a video of one of my favorite Mahler symphonies, Symphony N.5:

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário